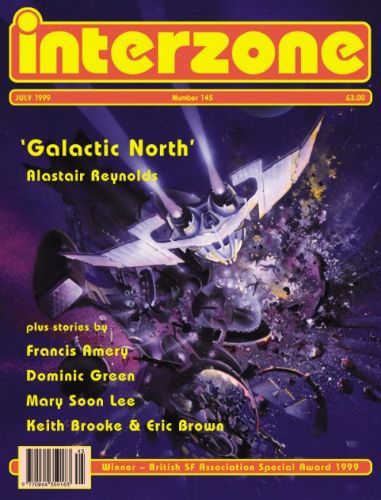

We lost power here for three days, so I did some romantic candle-lit reading of Alastair Reynolds' collection

Galactic North, a book I've been meaning to get to. I'm glad I did. These are romances in the older, literary sense with a touch of mystery and a cargo hold full of wild speculative conceits, some of which span the galaxies.

I belated realized what may have bounced out earlier attempts: The language on rare occasions is strained by office-report-style nonfiction and jargon ("Most of them had dispensed with holographics, projecting entopics beyond their personal space"), but one merely plows forward for the clever plots and speculative pleasures which outweigh minor, transitory strains. In fact, I read these all twice with pleasure to admire their craftsmanship.

Reynolds opens with "Great Wall of Mars." Of the collection, this story feels like the universe extends beyond the edges of the story. It feels rich enough to be a novel but whittled to a novella. This alone would make it most readers' favorite.

Two brothers, Warren and Nevil Clavain--both soldiers and politicians--disagree what they should do with Mars, which is infested with Conjoiners, people who have joined their minds into a gestaltic state. Nevil is sent down to Mars as a diplomat to get the Conjoiners to stop trying to escape their quarantine on Mars. However, he crashes into giant worms that aren't supposed. The Conjoiners throw down a rope and help him up. One even sacrifices his life.

Inside, Nevil learns not only of Conjoiner lifestyle but also of his brother's betrayal, leaving him stranded with alien humans who are about to be destroyed. The Conjoiners have other plans, plans involving the Wall of Mars protecting the air on the part of Mars that has been terraformed, and plans involving the moon.

Students interested in physics might be impressed with the novel use of orbits and gravity.

"Glacial" has the opposite effect of the previous tale: a novella with the pacing of a novel. Nonetheless, it's a fine speculative mystery that kept me guessing. I thought he hadn't played fair with the reader, but in fact, he had. Like the last, a grand speculation beats this one's heart. Plus, we get to watch the characters from "Great Wall of Mars" develop further--enough so that this reader is curious to read more.

Nevil and crew find a deserted colony on a distant ice planet where previous colonists studied its slow-moving worms, crawling through the ice. In a deep crevasse lay a man--Setterholm according to the name on his suit--whose helmet had popped off. He'd written "IVF" into the ice before he died. Other bodies are found--their quarters laced with a terrestrial poison that would have driven them insane. One man had frozen himself, whom they are able to revive. However, he provides little new information. Nevil finds his suspicions raised even though the man is good with Nevil's adopted autistic child--better with her than Nevil is.

This story explores intelligence and what that is.Both stories captivate.