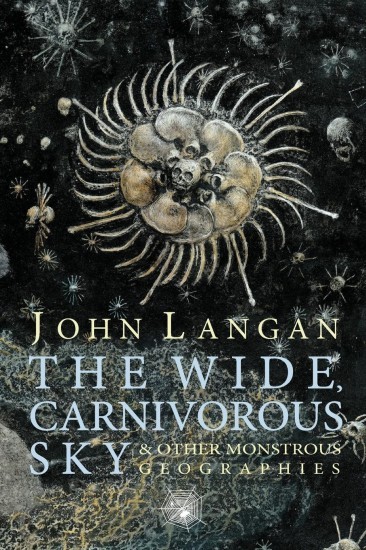

John Langan's collection, The Wide, Cavernous Sky

is up for the Bram Stoker award.

When you become a teacher, you can no longer read about teachers the same: This guys's nice, that a jerk; this one can teach, that cannot. You know, oversimplified. You have a new filter for student protagonists misinterpreting teachers because the student's perception of events can be narrow, only seeing through their own lives.

Students have asked about a teacher, "You like that guy?" or conversely, from teachers, "You like that class?" Yeah, you would, too, if you knew what they were going through.

Some teachers are "jerks" because it

is a power trip, but most are actually nice people who let students get away with things and get away and get away until the teacher's fed up and snaps. They told the student to do X, but the student didn't do it. The teacher didn't back up threats because he didn't want to hurt the student, so the student walks all over the teacher's commands. And then the student's surprised when the teacher blows up. "What's his problem? He let me get away with not doing X before."

To avoid that, some teachers act, to quote Langan's tale, all "hardass." [cut text talking about the hidden complexities of the job.] It's far more complicated than I imagined before teaching. That's why teachers complain and many don't try: "Until someone teaches me differently, I'll put my head down and plow ahead doing what I know how to do."

I bring this up because this story is about a "hard" teacher who has students, younger and dirtier than he's used to, silently enter his classroom, frighten him, trip him, and eat him.

How you interpret this tale has a lot to do about where you're coming from. Had I read this before teaching (despite having a mother in the profession), I'd have thought, "Mean old teacher gets comeuppance. Okay, moving on."

Now it's different. It reads more dream-like: a tale of an educator who fears the future, how he'll cope (or not) with the new generation. He has done it such and such a way for years and now meets resistance. Even though he tries to help the kids, he's eaten alive.

The latter interpretation is more nuanced, so let's grant that one.