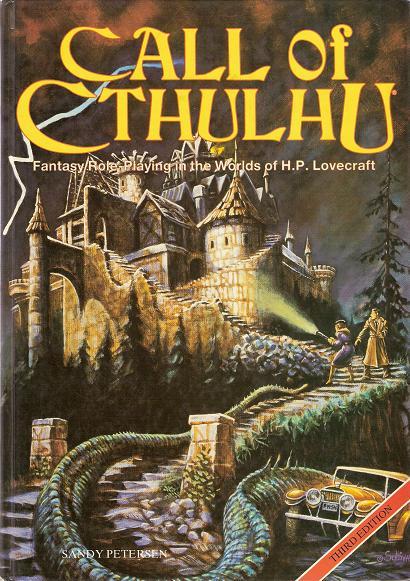

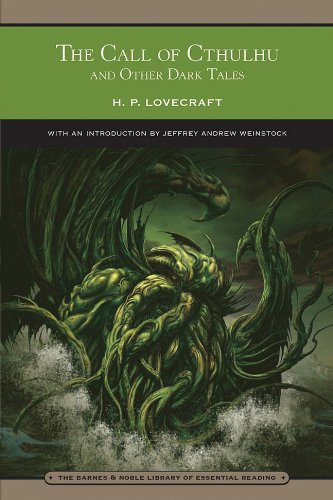

First appeared in Weird Tales, reprinted by T. Everett Harré, August Derleth, Peter Haining, Les Daniels, David G. Hartwell, Robert M. Price, Leslie Pockell, S. T. Joshi, John Gregory Betancourt, Colin Azariah-Kribbs--gaining more import in later years. It has spawned a movie, role-playing games and a radio drama.

First appeared in Weird Tales, reprinted by T. Everett Harré, August Derleth, Peter Haining, Les Daniels, David G. Hartwell, Robert M. Price, Leslie Pockell, S. T. Joshi, John Gregory Betancourt, Colin Azariah-Kribbs--gaining more import in later years. It has spawned a movie, role-playing games and a radio drama.Due it's piecemeal construction (a format I'm usually fond of if the sum is more than the parts) and Lovecraft's focus on mood over plot, this story challenges summary--at least, the through-line is tenuous.

I. The Horror In Clay

The narrator finds an evil-looking statuette made by an artist who, like many artists during a certain period in New England, became sensitive to vile dreams and visions. The narrator's uncle had the artist write down what he half-remembered of his dreams, which mostly consisted dripping caves and a half-seen monster.

II. The Tale of Inspector Legrasse

II. The Tale of Inspector LegrasseThe reason Professor Angell is interested in these dreams is because he'd run into a New Orleans cult, which had a similar sculpture. Their voodoo is more vile than any other.

After deaths and arrests, they find the cult is based around beings who came to Earth and slept, waiting to be revived and bring doom.

The narrator is suspicious of his uncle's death.

III. The Madness from the Sea

After meditating on the confluence of events, the narrator gets a hold of papers to locate this beast on a Pacific island. Cthulhu is awakened. They barely escape with their lives.

Commentary:

While Robert E. Howard and Michel Houellebecq consider this one of Lovecraft's best, E. F. Bleiler called it "a fragmented essay with narrative inclusions". Both views shed insight. The piecemeal effect creates a sense of deep-time, as if this has a long history. The style is much like an essay, but much of Lovecraft has a distancing effect as if it were an essay written more for veracity than for moving the reader. Events are told at a distance both in time and at a remove through secondary narrators. We do not feel the events directly.

While Robert E. Howard and Michel Houellebecq consider this one of Lovecraft's best, E. F. Bleiler called it "a fragmented essay with narrative inclusions". Both views shed insight. The piecemeal effect creates a sense of deep-time, as if this has a long history. The style is much like an essay, but much of Lovecraft has a distancing effect as if it were an essay written more for veracity than for moving the reader. Events are told at a distance both in time and at a remove through secondary narrators. We do not feel the events directly.In fact, both of these effects are often seen. It's fascinating the amount of effort Lovecraft goes to prove veracity. Whereas if a modern author had a character say, "I am not insane!", we would automatically categorize him as such; with Lovecraft we tend to trust his verification, as events appear to back up testimony. Moreover, it is generally the rational who go insane--lovely paradox--as perhaps they must if they encounter true knowledge of the universe. So why does Lovecraft verify?

No comments:

Post a Comment