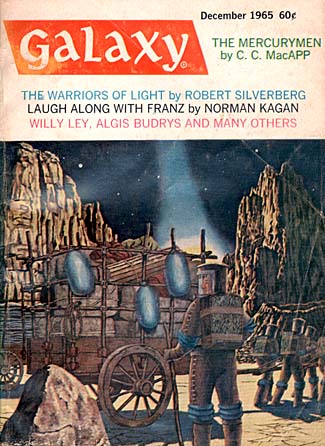

First appeared in Frederik Pohl's Galaxy. It won the Hugo, Nebula and Prometheus awards. Reprinted in several major retrospectives by Damon Knight, Donald A. Wollheim, Terry Carr, Frederik Pohl, Dick Allen, Willis E. McNelly, Leon E. Stover, Thomas E. Sanders, Isaac Asimov, Daniel Roselle, Bernard C. Hollister, Charles W. Sullivan, Leo P. Kelley, Martin H. Greenberg, Patricia S. Warrick, Bonnie L. Heintz, Frank Herbert, Donald A. Joos, Jane Agorn McGee, Rich Jones, Richard L. Roe, Leslie A. Fiedler, Arthur C. Clarke, Jerry E. Pournelle, John F. Carr, Ben Bova, Martin H. Greenberg, Applewhite Minyard, David Hartwell, Orson Scott Card, David G. Hartwell, Jack Dann, Gardner Dozois, Rob Latham, Veronica Hollinger, Joan Gordon, Istvan Csicsery-Ronay, Jr., Arthur B. Evans, Carol McGuirk, John Joseph Adams.

First appeared in Frederik Pohl's Galaxy. It won the Hugo, Nebula and Prometheus awards. Reprinted in several major retrospectives by Damon Knight, Donald A. Wollheim, Terry Carr, Frederik Pohl, Dick Allen, Willis E. McNelly, Leon E. Stover, Thomas E. Sanders, Isaac Asimov, Daniel Roselle, Bernard C. Hollister, Charles W. Sullivan, Leo P. Kelley, Martin H. Greenberg, Patricia S. Warrick, Bonnie L. Heintz, Frank Herbert, Donald A. Joos, Jane Agorn McGee, Rich Jones, Richard L. Roe, Leslie A. Fiedler, Arthur C. Clarke, Jerry E. Pournelle, John F. Carr, Ben Bova, Martin H. Greenberg, Applewhite Minyard, David Hartwell, Orson Scott Card, David G. Hartwell, Jack Dann, Gardner Dozois, Rob Latham, Veronica Hollinger, Joan Gordon, Istvan Csicsery-Ronay, Jr., Arthur B. Evans, Carol McGuirk, John Joseph Adams.Summary:The Harlequin is disrupting a future dystopia ruled by time or, rather, the Ticktockman. He holds the cardioplates of its citizens and can end peoples' lives prematurely if they are late to work, etc. The Harlequin slows schedules with a $150,000 in jelly beans gumming up slidewalks, badgers shoppers not to be slaves to time, and eludes capture (getting would-be captors caught in their own web).

Analysis:This has one of Ellison's patent-pending titles that simultaneously intrigues, conjures the story and its theme if obliquely. This tale provides an intriguing contrast to "I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream," which has a similarly loaded title.

The latter story, however, at first appearance seems simple enough but proves to be thematically elusive or at least complex. This story's theme, on first glance, feels elusive but turns out rather simple if compelling. It is spelled out immediately from Henry David Thoreau's "Civil Disobedience":

"The mass of men serve the state thus, not as men mainly, but as machines.... there is no free exercise whatever of the judgement...they put themselves on a level with wood and earth and stones."Men choose to become machines--as they did in "I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream," albeit to a different effect.

What surprised and disappointed as a lad yet empowers me as an adult--coming midway into the story--was that the Harlequin was an ordinary man, in love with an ordinary woman. They have a spat about his extracurricular activities and lateness (later, when he's told that his wife or girlfriend ratted him out, the exchange about whether she did or didn't takes on a different flavor).

Although the theme is somewhat clear, the ending is elusive. It involves at least three possibilities:

- Harlequin confesses, gets killed, yet somehow infects the Ticktockman with anti-clock mentality. This seems least probable since most in power would want to cling to that power.

- Harlequin somehow escapes, forces the Ticktockman to believe he is the Harlequin, gets the Ticktockman to confess as if he were the Harlequin and gets killed while the Harlequin becomes the Ticktockman. We aren't witnesses to this complicated event. While Harlequin might be trickster enough to pull this off, is the Ticktockman truly gullible enough to fall for an identity switch? Nothing in the story really leads us to this.

- Harlequin is the Ticktockman. Both mask their identities. The Ticktockman's irregularities at the end match the Harlequin's usual habits. We don't know if this is unusual for the Ticktockman, but being in charge, he could probably get away with it.

Finally, there is a temporary irony (or hypocrisy) that loses its meaning if Harlequin is the Ticktockman:

"[H]e was called the Ticktockman. But no one called him that to his mask.

"The cardioplate here in my right hand is also named, but whom named, merely what named."We know what the Ticktockman is--the Master Timekeeper--but not who he is since he is masked.

The theme isn't much altered in the first two ending possibilities. But the third suggests that the revolutionary and the problematic cogwork-makers sprout from the same scarcely sane source. The theme alters considerably. It might be paraphrased by The Who's "Won't Get Fooled Again":

"Meet the new boss. Same as the old boss."

No comments:

Post a Comment