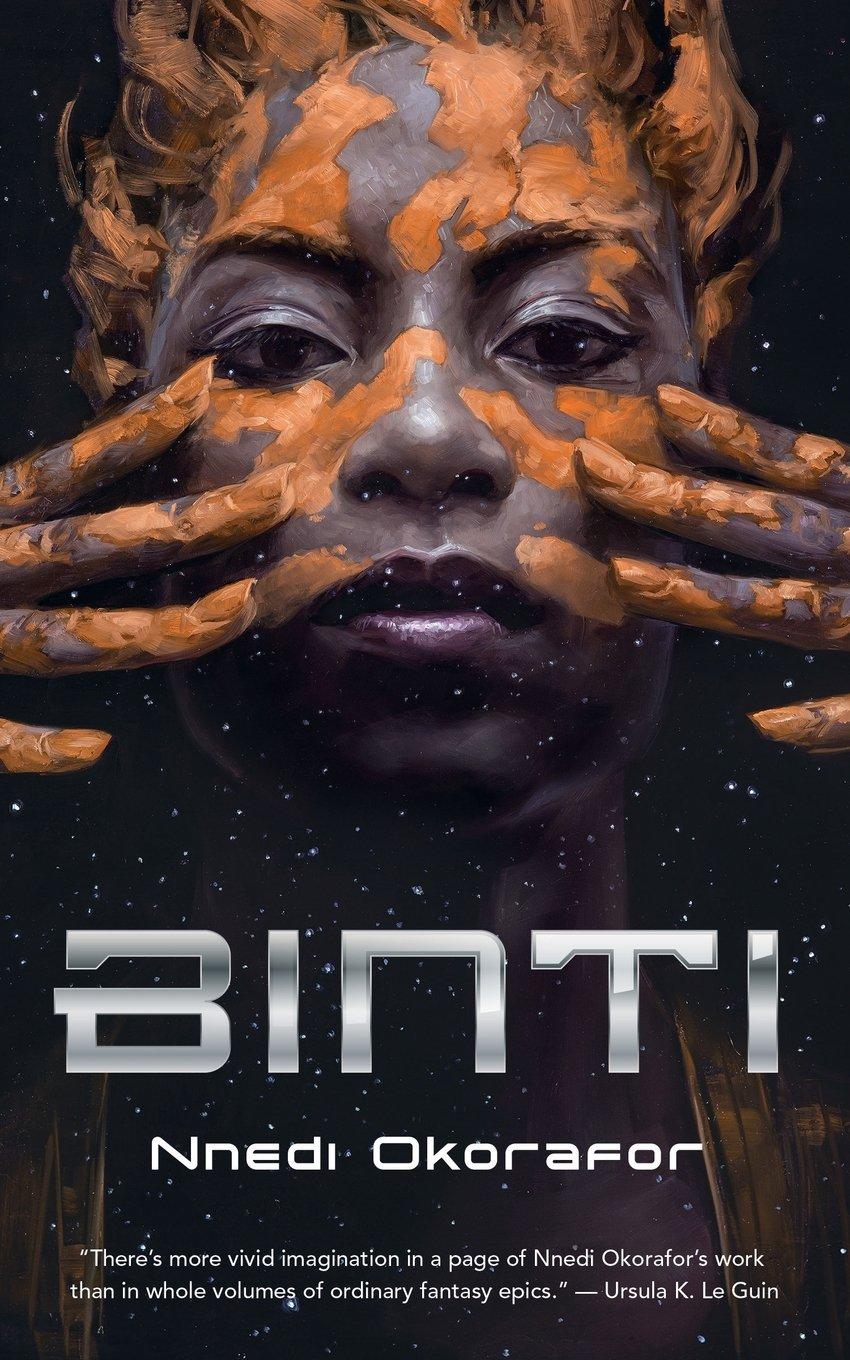

I haven’t rhapsodized on science in literature in a while, so it’s time.

While reading Nnedi Okorafor’s Binti, I paused to mull over the use of “force field” on the second

page. She wasn’t using in the accepted sense, which is usually a nonsensical

energy defense shield against attacks. At least at the moment, these force fields

seem improbable. The word “force,” in this case, probably refers to some

military sense, as in the Air Force.

It probably does not refer to force in the scientific sense

of something that place a force upon a mass to cause it to accelerate. It

usually absorbs energy and somehow sustains damage as a physical object might

although who knows why it should do so if there’s nothing physical to damage. Perhaps

the excess energy in fed into some device that can only absorb so much energy.

But usually there’s a percentage loss or gain. “Shields are at 47%, Captain!”

Whatever that means. I suppose we know that 60% is a barely passing grade in school,

so we feel safe until it drops to the dreaded 59%. “We can only sustain one more hit!” is a

little more clear if a little less scientific seeming.

It probably does not refer to force in the scientific sense

of something that place a force upon a mass to cause it to accelerate. It

usually absorbs energy and somehow sustains damage as a physical object might

although who knows why it should do so if there’s nothing physical to damage. Perhaps

the excess energy in fed into some device that can only absorb so much energy.

But usually there’s a percentage loss or gain. “Shields are at 47%, Captain!”

Whatever that means. I suppose we know that 60% is a barely passing grade in school,

so we feel safe until it drops to the dreaded 59%. “We can only sustain one more hit!” is a

little more clear if a little less scientific seeming.

Here’s Okorafor’s usage:

“Once on, the transporter worked better when I didn’t touch it.... When nothing moved, I chanced giving the two large suitcases sitting atop the force field a shove. They moved smoothly and I breathed a sigh of relief.”

This is a “transporter” that apparently moves things via a

force field, which is clearly not a defensive energy structure but perhaps a

more scientific (or scientific seeming) than the military one used in SF. What

is it?

We have magnetic fields, which we visualized in grade school

by dumping iron filings on a sheet of paper which had a magnet underneath

it—all of those semi-circles converging at the poles. The earth has its own

magnetic field which we can see in a few ways: 1) a compass points to the poles

by aligning with the fields in more the same way an iron filing does on a sheet

of paper. 2) The aurora borealis or the northern lights is a light show you get

when the earth is bombarded by a lot of sun radiation and it all gets funneled

into the poles where it interacts with the atmosphere. “That’s a force field!”

someone might cry enthusiastically. Yeah, it sort of is. Except there are no

atmospheres surrounding space ships and force fields explode physical objects

and lasers.

But clearly this is something that transports. You might

think of gravity as a field with just one pole, where the closer it get to the

gravitational object, the greater the gravity. The closest I could imagine would

be an object works the opposite of a gravitational field. Imagine a planet that

didn’t hold you down but shoved you away. To transport, it would need to first

overcome gravity (to get off the ground) and then match it so it can hover. Cool

concept. Since we’re dealing with acceleration, I doubt it could come off

smoothly.

But then in order to move the luggage, you have to move the

force field which is the tricky part. How do you do that? It is a field, which

means it acts the same in all directions. As you approach it, it pushes you

away. Luckily, you have the earth and friction on your side, but unwary

children might get knocked down. You might have to lean toward it—at least

initially—to get it moving.

But how do you turn and stop it? With great difficulty. With

it on, it’d be a little like trying to guide a ball rolling downhill in that

you aren’t maintaining the ball’s movement but guiding or herding. You might

just turn it off and let friction stop it, and then on again once you change

directions.

But how does it generate a field? Magnetism does so via the

movement of electrons, or aligning unpaired electrons. Gravity works by the

proximity of masses. But this does the opposite of gravity. There used to be

the staple of SF of having “anti-gravity” devices in your equipment—whatever

that was. Perhaps they made a things have a negative mass. If so, how do you

neutralize the effect since it is usually not behaving as if it were acted on

by a force? I have no answer for that.

Crazier still, the luggage is sitting on top of the

transporter, so could it actually be a part of the transporter’s “system”—a

term meant to include the luggage as part of what acts outward, of what pushes

things away? Yet the luggage is on the outside and should be one of the things

pushed away. Could it be levitated, just as the transporter levitates?

Possibly, but what then would be the point since the expenditure of energy

would likely be wasted? Why not use a cart? And levitation would be in a

precarious situation should the transporter change directions... unless the

force field were bowl-shaped to help keep objects centered on top.

Maybe someone else has a better idea how this force field

works. Interesting to speculate on, nonetheless.

No comments:

Post a Comment