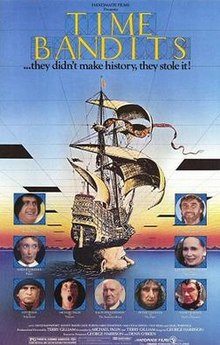

In 2017, Terry Gilliam was inducted into SF Hall of Fame and received the 2009 BAFTA Fellowship for lifetime achievement. In 1976, he shared with his co-writer Terry Jones, a British Fantasy award. For Time Bandits, he received a nomination for the same award. Empire magazine listed it as #22 of children's movies, and as Time's "Top 10 Time-Travel Movies".

Time Bandits, I loved as a kid, as much as I loved nearly all of Terry Gilliam's work, even the ones I'm not supposed to. As a kid, I must have loved all the crazy plot shifts in Time Bandits, which still are fun. It retains some thought-provoking good vs. evil, bunched at the end. This is the only film I can recall where the protagonists were all short. But why wasn't I disturbed about the ending as a kid?

It has fallen on my nebulous list of films, from the upper stratosphere of brilliance--probably due to the semi-picaresque nature--but not as far as I'd thought.

The following spoilers may affect some people's enjoyment, but for those who want to keep their enjoyment active, it should enliven their viewings. I leave some key things out, but of course, you can watch the movie yourself and return to read.

First, it opens with a marvelous commercial where it talks about how wonderful modern conveniences are, how they free up our lives so we can live as we want to, and we get to view a family watching TV and/or reading what seems, not necessarily life enlivening stuff (which is an alternate interpretation of the title). The wife complains about differences between a neighbor's and her microwave--one being 7 seconds faster at heating up. And of course, this calls into question what we are freeing up our lives to do. The speed of the microwaving suggests that the timeline begins in some near future (Yes, I realize, this scene is a joke, but it's also serious in terms of contemplation. So much information in so tight a space.)

There's a TV show called "Your Money or Your Life," and I must admit to not fully grasping this one, which must be critical. Clearly not a game-show phrase, but what a robber says when he wants you to choose between giving him your money or dying. But here, it's a game show. I don't think there is (in the movie's universe or any other) a realistic game show unless again that society is less interested in human life that people are willing to gamble their life on a TV game show, which I'm dubious about. Whenever we do see these game shows in literature, I think we only buy into them when there is an element of coercion which does not seem to be happening here. Unless I'm mistaken. Maybe life means less in a world of convenience (or so Gilliam predicts?). But if we simplify this as a metaphorical choice between things (You can work for a good living or live a life that involves family), then I'd buy into the equation, but I doubt you could make a game-show out of that. That, though, is an interesting way to frame our lives. I'll return to this in a different section.

The game show comes into play toward the end when the evil one appears with his parents, but first we have to discuss reality.

What is reality and what is imagination? On the kid's [Kevin's] wall are drawings and images of everything he's about to experience. Is this a dream, a lively imagination, or reality? But the father suggests that it is all real by saying Kevin is making a lot of noise in his bedroom. The only explanation is that these fantastic events are reality. Yet how did he "predict" these events in the past with his drawings? So is it real or not? My feeling is that we are meant to these are imaginings fleshed out in reality since there often is evidence proving fantastic events even after everything has been reset to reality. Of course, it's possible that we are still within a dream world, but then we have no idea what reality is in this world.

So when his parents appear as part of the game show, we learn that they were part of the illusion of the evil one. But if true, why were they drawn to touch the pure concentrated evil?

It's hard to know what to make of what happened to Kevin's parents? Is it all a dream or imagination, or did imagination create reality, or did a capricious god who seems to be restoring order in other ways, suddenly allow this tragedy to occur? If so, why? Caprice? Anger over behavior within someone else's imagination or illusion?

We laugh at us humans in the opening scene, at our "problems," but then we have arrive at the end with a more serious problem and it's related with a similar jocular tone. Do we laugh again, or do we pull back a bit and wonder about how we should feel given the circumstances? Is the first scene altered in our mind? or the last?

Fascinating to ponder, whatever our conclusions.

No comments:

Post a Comment