For more a deeper look and for other ways of seeing this story, see this post. It has been viewed ~1500 times.

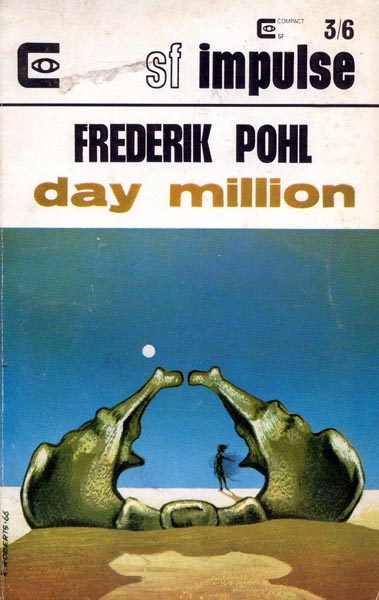

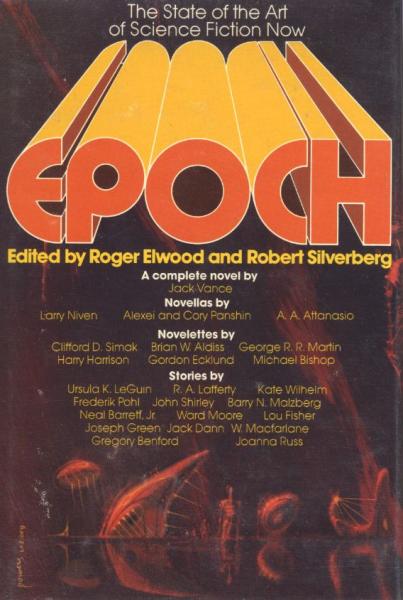

First appeared in Frank M. Robinson's Rogue. Reprinted in nearly a dozen major retrospectives, byAnn VanderMeer & Jeff VanderMeer, James Patrick Kelly, John Kessel, Leigh Ronald Grossman, Arthur B. Evans, Gardner Dozois, Martin H. Greenberg, David G. Hartwell, Kathryn Cramer, Ursula K. Le Guin, Brian Attebery, Robert Silverberg, Josh Pachter, Martin H. Greenberg, James E. Gunn, Patricia S. Warrick, Joseph D. Olander, Brian W. Aldiss, Harry Harrison, Pamela Sargent, Robin Scott Wilson, Damon Knight, Dick Allen, Donald A. Wollheim, Terry Carr, Val Clear. Both Lester Del Rey and James Frenkel considered this one of Pohl's best.

First appeared in Frank M. Robinson's Rogue. Reprinted in nearly a dozen major retrospectives, byAnn VanderMeer & Jeff VanderMeer, James Patrick Kelly, John Kessel, Leigh Ronald Grossman, Arthur B. Evans, Gardner Dozois, Martin H. Greenberg, David G. Hartwell, Kathryn Cramer, Ursula K. Le Guin, Brian Attebery, Robert Silverberg, Josh Pachter, Martin H. Greenberg, James E. Gunn, Patricia S. Warrick, Joseph D. Olander, Brian W. Aldiss, Harry Harrison, Pamela Sargent, Robin Scott Wilson, Damon Knight, Dick Allen, Donald A. Wollheim, Terry Carr, Val Clear. Both Lester Del Rey and James Frenkel considered this one of Pohl's best.

Summary:

In the near or far future, a boy and a girl fall in love. But they are not like any boy or girl that we today might know.

Discussion:

The Aesthetics:

Someone asked me what the most disappointing but most lauded story I've read. This one came to mind. The biggest problem is the lack of fictive dream as John Gardner called it. We never get to fall in love with our characters who are supposed to fall in love with each other. This was my complaint although one might focus on other issues. I don't care if I agree or disagree, but the aesthetics should be up to par. One could slip into and out of the fictive dream, which would probably be the best scenario in a situation like this, no matter how difficult the future might be to explain.

One major unanswered question: How and why is the narrator talking to us in this way? What is preventing our understanding? It addresses us (if we indeed are the adressees in the speaker's tale) as if we will object, but I doubt few SF readers actually ever do. If only the story were more pinned down in time and place, it might have suggested more of the fictive dream.

This suggests that the story is aimed in a different direction. Much as I like stories that break the fictive dream, we are rarely immersed in it here. Pohl could have done so as he had the skill, but chose not to. Perhaps he didn't want to. Why not? Did he not want or was he incapable of delivering the strangeness? Was he writing at the edge of what he could comprehend? Or was he purposefully thwarting expectations?

Robert Silverberg praises this "style" in Worlds of Wonder, yet almost in the same breath suggests it shouldn't be done again.

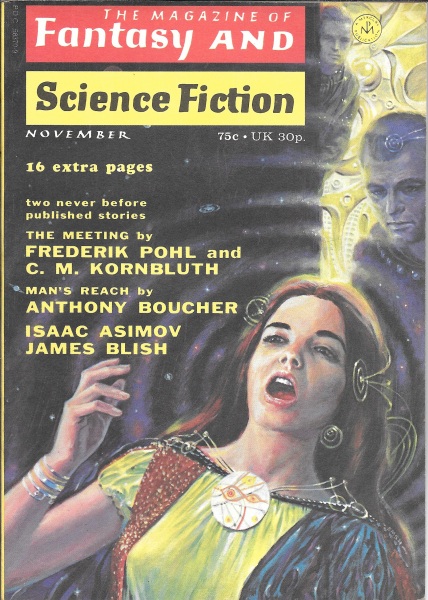

In this era, a number of writers were trying to rewrite what fiction

means. This is probably why Harry Harrison and Brian Aldiss included it

in the Nebula Award anthology, despite it apparently not making the cut.

It may have been considered part of the New Wave, which Aldiss

(especially) and Harrison sometimes championed.

The Thumbed Nose at Normies:

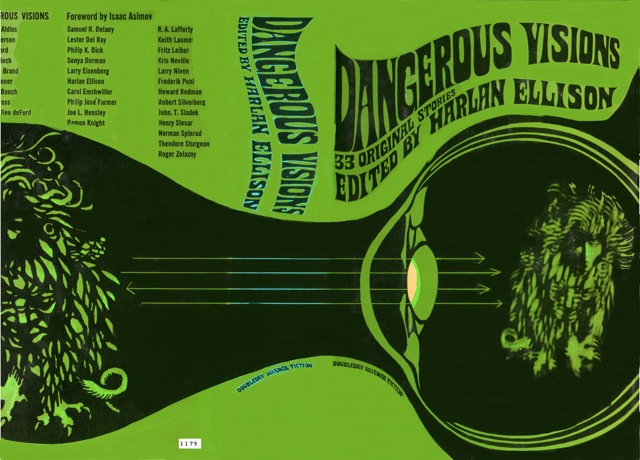

The British New Wave was more aesthetically driven while the American New Wave (exemplified by Harlan Ellison's Dangerous Visions) was more taboo driven. This story conveniently fits both parameters. Clearly there was cross-pollination between the two. It feels like a Dangerous Visions story, and perhaps it helped launch the idea in Ellison's brain.

This was first published in the men's magazine--intended as a rival to Playboy--as edited by Frank Robinson who was gay, which is a curious combination yet explains its publication.

As suggested above, the style itself is a thumbed nose at our conception of story should be but it also rejects our idea of normative sexuality. But it does so, so strangely. Yes, it is still trangendered individuals, but in a way that it is still normal. If it could be labeled as such. It wants to make the strange as normal as possible. It is but is not.

However, the future changes genders based not on the individual but on what outsiders view the genetics should be. In a sense, it doesn't understand that it is presenting the same problem to the next generation. It isn't even nature developing one's gender, but human beings telling people what their gender is. Pohl's narrator suggests this is just like giving a scholarship to Julliard for people talented at making music, but this is done without consent before an individual could decide for themselves.

The Science:

This suggests one of the potential scientific problems with the text. On one hand, maybe in the future, we think we might be able to guess by an arrangement of genes who will desire might desire to be transgender, but it neglects our understanding that not only is phenotype determined by genetics developing, which influences the development of other genes but also by nurture. Also, it would be far simpler to add or remove the Y chromosome, so that one would not have to continually repress one's gene expression. Yet the Y and the X are maintained as is. But it still seems improbable that one could guess what phenotype one would want to express. Instead of freeing of gender, it might be a shackling of gender. This might create more problems than it prevents.

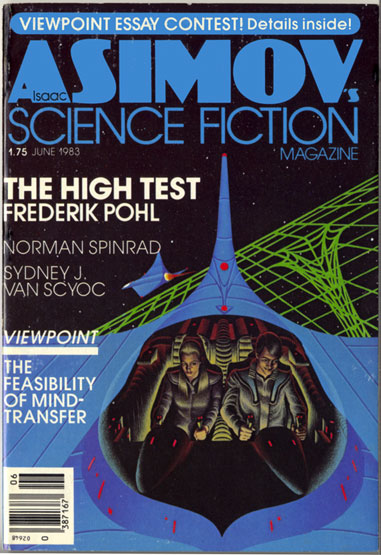

When I first read it, I didn't challenge its suppositions, assuming "Day Million" meant [a] Day [a] Million [years from now]. I think (the text says about 10,000 years from now, so maybe I accepted that). Some far future, anyway. In Pohl's essay "On Velocity Exercises" from the Those Who Can anthology (see discussion of that essay here), that this was supposed to be a million days from the beginning of the Christian era. That would mean, more or less, Novembber 23, 2737. That would have been ~770 years from when Pohl originally wrote this.

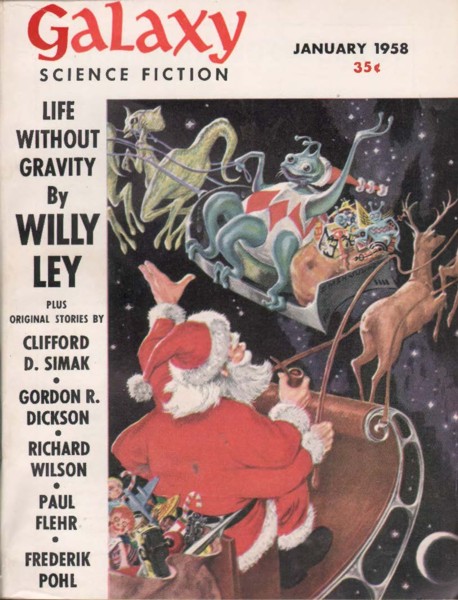

However, if one were to project from the publication date, then it would suggest Christmas Eve or Christmas in 4703. Either way, we are still a far cry from 10,000 years from now. Perhaps Pohl rounded and did a quick mental calculation using 100 days in a year instead of 365.25 (accounting for leap year). This suggests that maybe Pohl wrote this a little too hastily, perhaps without double-checking himself.

One character has a centrifuge for a heart. That doesn't make sense based on what we know about centrifuges which separate the parts of a solution/suspension such as that contained in a cell in order to study the parts of each. Why would a creature want to separate out the parts of their blood? It would probably be poor at holding oxygen post-separation. Or maybe the centrifuge is more metaphorical, suggesting that the blood is flung out to the parts of the body by some high-speed rotary device. However, one problem would be a huge blood pressure, which means a different constitution from what we have today, or they'd all be dead seconds after creation of the heart. The other problem would be the difficulty of oxygen distribution, which would be a lack of time for this to occur.

It also discussed osmosis as one method of oxygen distribution, which make sense unless we are talking about beings at least as small as frogs with large surface areas.

On the Whole:

As the above link suggests, there is much to appreciate. It is flawed. But it is probably best appreciated as a kind of speculative essay.

First appeared in Frank M. Robinson's Rogue. Reprinted in nearly a dozen major retrospectives, byAnn VanderMeer & Jeff VanderMeer, James Patrick Kelly, John Kessel, Leigh Ronald Grossman, Arthur B. Evans, Gardner Dozois, Martin H. Greenberg, David G. Hartwell, Kathryn Cramer, Ursula K. Le Guin, Brian Attebery, Robert Silverberg, Josh Pachter, Martin H. Greenberg, James E. Gunn, Patricia S. Warrick, Joseph D. Olander, Brian W. Aldiss, Harry Harrison, Pamela Sargent, Robin Scott Wilson, Damon Knight, Dick Allen, Donald A. Wollheim, Terry Carr, Val Clear. Both Lester Del Rey and James Frenkel considered this one of Pohl's best.

First appeared in Frank M. Robinson's Rogue. Reprinted in nearly a dozen major retrospectives, byAnn VanderMeer & Jeff VanderMeer, James Patrick Kelly, John Kessel, Leigh Ronald Grossman, Arthur B. Evans, Gardner Dozois, Martin H. Greenberg, David G. Hartwell, Kathryn Cramer, Ursula K. Le Guin, Brian Attebery, Robert Silverberg, Josh Pachter, Martin H. Greenberg, James E. Gunn, Patricia S. Warrick, Joseph D. Olander, Brian W. Aldiss, Harry Harrison, Pamela Sargent, Robin Scott Wilson, Damon Knight, Dick Allen, Donald A. Wollheim, Terry Carr, Val Clear. Both Lester Del Rey and James Frenkel considered this one of Pohl's best.