"The person has received a well-known and significant award or honor, or has been nominated for one several times."I am going to assume that Magnolia677 is just playing by the rules and not someone with an axe to grind.

Interesting questions arise: "What is significant?" "What makes a writer and his work worth remembering?" One can apply the same questions to Wikipedia itself: Who cares if an article is deleted from them or not? Who are they?

However, it is a go-to, community fount of information, which academics tend to discredit, but let's say it is worth keeping because the above quote makes fascinating dissection.

- Why does someone need to win an award? I'm guessing it isn't the only measurement that Wikipedia uses when deciding to include or exclude.

- Bestsellerdom or popularity will also be a measure (see Eric Flint below).

- Likewise, Shakespeare and John Milton didn't win awards, yet they are included. There, the measure is academic appreciation (which, one might say, is what the Mythopoeic award is).

- Moreover, even Wikipedia acknowledges that William Faulkner is not known for his award-winning works. Therefore, despite the above quoted claim, this really is not a selection criteria for inclusion in Wikipedia for authors.

- Richard Parks has been nominated for five awards, won one. How many is several? Is five not several? (See below for further discussion of what even means to be nominated for the best.)

- What is well-known? What is significant? The Hugo award is probably the most famous genre award. The award is exclusive to a group of those who pay to vote and/or attend a convention [World Con]. Last year, they had ~4200 attend and ~7000 with voting privileges. The convention supporters are probably more likely to vote than not. However, voters won't vote for every category. So for any category, let's guess that there's a 50-75% involvement. Let's say 5,000 vote. Let's compare that to the Science Fiction Age poll. Let's say of a 50-60,000 subscriber base, only ten percent vote. In terms of voter numbers, the awards may be roughly equivalent.

- Caveat not in Parks's favor: Note, however, that SF Age Reader's Poll has only one magazine that is up for an award, so the selection/competition is narrower.

- Caveats in Parks's favor: 90%+ of the World Con voters did not read every story in every magazine. Therefore, it is probably safe to call the winner of an SF Age poll, comparatively, as significant as, say, a Hugo award nomination.

- I've read the story in question. It is good but not a major story. It is better than some stories that won major awards.

- Not including his award-nominated stories and novellas, Richard Parks has had fourteen stories included in various genre retrospective and year's best anthologies. These are selected by respected writers or editors of the field. Let's call these selected stories, long-listed "award" stories. Let's assign them the worth of half a nomination. That would give Parks seven more nominations (if you prefer a third, then it would be five more nominations). So we end up with the equivalence of ten to twelve award nominations. Is that enough for significance?

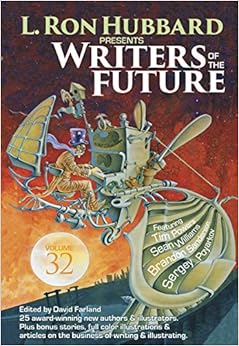

- Related to #4, if you [who question a writer's significance] agree that someone is significant enough to have a Wikipedia page, and that person says that the writer is significant (whether via book blurb or collecting that author's work or somehow stating that Parks's works stand among the best released in the past, then you must agree the writer in question has significance. (This, of course, leaves out all the Wikified editors like Shawna McCarthy who printed Parks multiple times.) Writers or editors who fit that bill:

- Kathryn Cramer (four reprints)

- David G. Hartwell (four reprints)

- Margaret Weis (one)

- Eric Flint (one--who has, by the way, not won as significant award or been nominated as often as Parks)

- Mike Resnick (one)

- Jonathan Strahan (one)

- Sean Wallace (two)

- Rachel Swirsky (two)

The discussion, however, is academic. His collection, Yamada Monogatari: Demon Hunter (see review), is significant--not the best of its year but among the best. This marks him as a writer worth reading and having a Wikipedia entry (were I to vote on this). Put another way: If Sir Arthur Conan Doyle deserves an entry on the basis of literary merit, then so does Parks.

His novel/collection was not well known enough that people turned to it for award nominations, which is a shame. Like Faulkner's best, sometimes good works do not get the awards nod. Still, people will be reading and passing on via word of mouth that Yamada will probably continue to sell beyond some award winners.

The author should gather his reprinted, award-winning and nominated shorter works into one massive "Selected Works" collection to see if that doesn't help tip the scale toward significance.