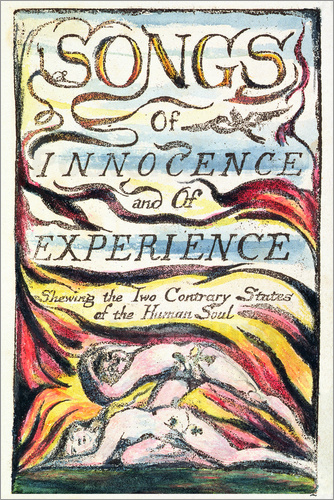

These were published in William Blake's 1789/1794 Songs of Innocence and Experience. These often but not always had mirrored poems, where one upon reflected upon another, setting up the contrast of innocence and experience, which is probably the most useful tool in examining these poems. The book's subtitle, as seen here, is another, underutilized tool:

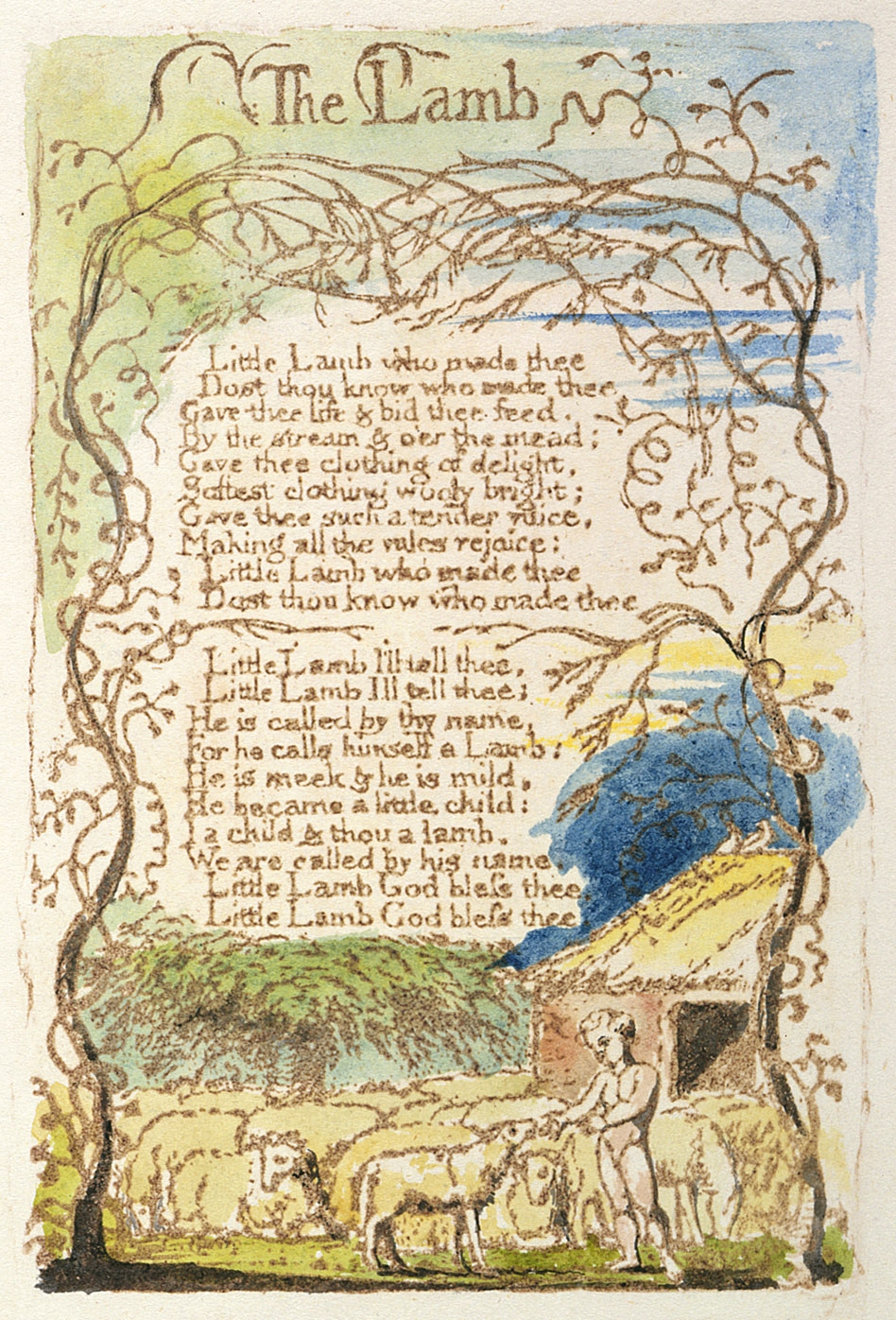

"Shewing [Showing] the Two Contrary States of the Human Soul""The Lamb" illustrates innocence, "The Tyger" experience. Commonly, "The Lamb," which the persona addresses to the lamb itself ("Little Lamb who made thee"), is seen showing God's sweetness in giving

clothing of delight,

Softest clothing wooly bright;

Gave thee such a tender voiceGod himself became a lamb.

By contrast, "The Tyger" is commonly read as at least a tentative questioning if not a critique of God. How could this fearful deadly predator be made by the same hand that made the lamb ("Did he who made the Lamb make thee?")? How can the God who makes good also make evil?

It may be saying these things, and I think it is important to keep in mind, but take a closer look at "The Tyger." The first stanza is the same as the last. In other words, it has symmetry. Within that symmetry, poem asks, "What immortal hand or eye, / Dare frame thy fearful symmetry?"

What hand or eye? Why, Blake's obviously. He just did it.

We have a frame followed by what one could describe as the wildfire of the Muse. The whole centerpiece is less a description of a tiger than the a poet's process:

In what distant deeps or skies.

Burnt the fire of thine eyes?

On what wings dare he aspire?

What the hand, dare seize the fire?

And what shoulder, & what art,

Could twist the sinews of thy heart...?

Did he smile his work to see?Art? Work? What else would God, a creator like the poet himself, do but smile with pride on his creation?

Do you doubt this interpretation? Try the next line:

"Did he who made the Lamb make thee?"Why, yes. Blake wrote both "The Tyger" and "The Lamb."

How about the subtitle of the collection: "[Showing] the Two Contrary States of the Human Soul"? He may be talking about God but more pointedly about humanity. So the same critique one just applied to God has to be applied to himself.

When we turn to the question of "The Lamb" [Little Lamb who made thee], we have to ask what a lamb is. Yes, a wooly animal. Yes, as stated in the poem itself, God (at least in Christian terms). Also, believers. And a child, too, is considered a lamb--a usage still somewhat common today. Now these lines read differently:

He became a little child:I a child & thou a lamb,We are called by his name.

God is a child, the lamb is a child, the poet narrator is a child, and all "called by his name." So God is a child is a lamb is a poet/creator. We all have the same name.

"Why, the nerve! Calling himself god and 'immortal!' "

That does take some balls. Maybe Blake is egotistical, but it makes the poems fascinating. For now we see our humanity reduced to contraries--formed of opposite poles. These aren't poems about innocence and evil--at least not so much--but of innocence and experience. Does the tyger have less right to exist? It does exist. It's already here, and it exists within us, next to the lamb. Are they at war? Are we at war with ourselves, our contraries? Let's rephrase our critique of God and point it at ourselves: "How can we who make good also make evil?"

Much as these poems seem simple, simplicity isn't Blake.