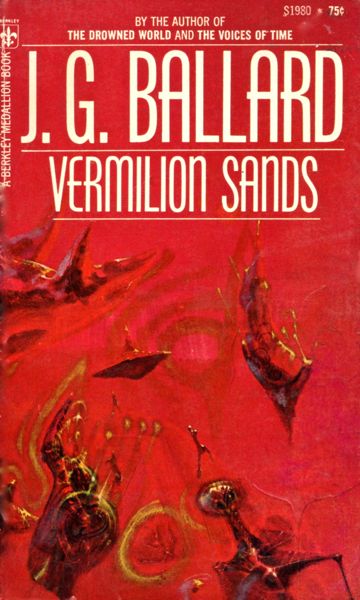

Eventually, the hub of commentary on the Vermilion Sands will be located here.

This story first appeared in Edward L. Ferman's The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, Judith Merril, Roger Zelazny, Edward L. Ferman, Martin Harry Greenberg, Joseph Olander, Frederik Pohl, Philip Hensher.

A group of cloud sculptors--some of whom have been undermining their own work--are commissioned by the rich, Leonora Chanel, to construct her portrait in the sky.

The story opens letting us in on their certain demise.

Commentary with Spoilers:

That the art is dependent on the shape of clouds, changed wind and sun, suggests the very destructibility and impermanence of art. Nolan seems to take an active part in its impermanence, pointing out death in the life of an infant:

"Illuminated by the afternoon sun [on the cloud sculpture] was the serene face of a three-year-old child....

"Nolan seemed unable to accept his own handiwork, always destroying it with the same cold humour....

"he worked away at the cloud, and then someone slammed a car door in disgust.

"Hanging above us was the white image of a skull."

The figure of Nolan might be a metaphor for Ballard's own art within the genre. See the discussion of Zelazny below, which might explain Lenore Chanel: "Let the rich choose their materials [out of which art is created]."

The character of Lenore Chanel seems to allude to two figures: Coco Chanel, the 20th century fashion guru, whose career started in what might be considered feminist revision of fashion, whose name still signifies the upper class, but whose relationship with the Nazis tainted her. Lenore is a doomed figure of pride yet adoration although it had been used by the Romantics as a personage prefiguring vampire literature. Ballard seems to have consciously used these and put Lenore in a cobra suit, an alligator suit, and peacock feathers.

Why Lenora chose these artists who attack their own art remains a mystery. Was she uninformed? Possibly, although that seems unlikely. Perhaps she had an invisible [to the narrator] self-destructive streak. Why send artists off to their possible destruction while they create your portrait? Wouldn't you fear their striking back through their art? Why mock the hunchback who is about to carve her face? It must be a kind of sado-masochistic desire to hurt and to be hurt. Or does she think that money will protect her from abuse? Yet she must know what these artists have done before, or why go to them?

There's also a bit of mystery in the style, where much of the description is evocative, brilliant and painterly:

"All summer the cloud-sculptors would come from Vermilion Sands and sail their painted gliders above the coral towers that rose like white pagodas beside the highway to Lagoon West. The tallest of the towers was Coral D, and here the rising air above the sand-reefs was topped by swan-like clumps of fair-weather cumulus. Lifted on the shoulders of the air above the crown of Coral D, we would carve seahorses and unicorns, the portraits of presidents and film stars, lizards and exotic birds. As the crowd watched from their cars, a cool rain would fall on to the dusty roofs, weeping from the sculptured clouds as they sailed across the desert floor towards the sun."

But then there are occasionally odd descriptions that are difficult to visualize:

"One was a small hunchback with a child’s over-lit eyes and a deformed jaw twisted like an anchor barb to one side."

Perhaps this is meant as a mirror to the art discussed: the grotesque. The other "anchor" in the story is the narrator's crutches, trying to anchor in the sand -- a sea metaphor without a sea, an anchor that cannot be anchored, and art that is ephermeral.

Nolan, sick of Lenora's cruelty and self-absorption, destroys both

Lenora, her edifice of opulence, and the art around her. The story's

ending mirrors "Prima Belladonna" a little too closely--the way Nolan and Jane

both die yet live on perhaps in reality or just in myth. Perhaps the

similarity explains why Ballard originally separated the two, and why he

brought them together in later editions.

It depends on which edition of Vermilion Sands you read whether this story is first or "Prima Belladonna" and this is buried toward the back. Perhaps the order is immaterial, but it does suggest the importance of the work to Ballard, or perhaps to the later editor at Jonathan Cape.

It's fascinating that the tale was included in the Roger-Zelazny-edited Nebula Awards 3, in which he states all of the stories were nominated for the Nebula awards; however, it isn't listed as being one of the nominees. Nonetheless, Zelazny not only includes the story but places it at the front, suggesting its importance to the whole volume:

"Ever play Max Ernst games by staring up at that tent of blue we prisoners call the sky? If so, I think you will appreciate this story. If not, you can always do it over again yourself by regarding Up. It takes a true architect of the nervous system and the environment, however, to not only play this game, but to play it well. J. G. Ballard, I submit, is one of the greatest cloud-sculptors I have ever witnessed in action.

"So put on the appropriate piece by Debussy, and bear in mind that despite Cervantes, last year's clouds are not so useless as they may seem. No.

"I chose to open the volume with this story, to set the Magritte-mood of reality twice removed and, perhaps because of this, twice as real."

This may have been in rebellion to the rebellion against the New Wave, which was in rebellion to the Old Wave or the then-traditional SF. Or maybe the nomination snub was just a rebellion against Ballard, who had been also publishing his dismal dystopias and The Atrocity Exhibition at the same time, experimentation with the very nature of storytelling itself.

Reminder: this is all speculation. Yet how did Zelazny not know that the story had not been officially nominated? How did his editors and publishers not know?

![Best Game Ever: A Virtuella Novel by [R R Angell]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51+szU3dpTL._SY346_.jpg)