First appeared in Terry Carr's Universe anthology series. Reprinted in retrospective collections by Donald J. Pfeil, Lester del Rey, Terry Carr, Isaac Asimov, Thomas F. Monteleone. It was a runner-up for the Hugo and Locus award (according to ISFDB) and a finalist for the Nebula.

Background:

Rotsler's art appeared in fanzines and was his first major impact on the genre, winning ten major awards from Locus and Hugos between 1971 and 1997. He did cartoons and made movies, of a kind [IMDB]. They don't seem to be high art although I doubt he'd have agreed when he made them, based on some of my readings of his own writings (see some of his quotes in the Youtube video below). Quotes like these (and perhaps this one from the story) seem to have made him an attractive person to be around:

"[Y]ou might be without money, but you are not poor."

"Bohassian Learns"--a story preceding this one in time and development--is discussed here. It suggests more about the writer's character and thought process.

The author grows as a literary artist in later novels, but it retains a very uncluttered SF style from the 70s.

This story seems tailor-made made for a man like Rotsler: A story about art, written by an artist. Except the writing is less artsy than philosophical--almost dialectical. One of my favorite quotes is this (albeit, from the novel, not the story), which I thought prophetic:

"Today the artist who cannot master electronics has a difficult time in many of the arts."

This next quote may or may not be true, but at least it illustrative of the writer and perhaps the story itself:

"The artist doesn't see things, he sees himself."

Rotsler's best quotes seem to set up expectations and break them in the next with some revelatory insight into the arts or human nature (as the first above and, again, see more quotes below).

A number of artists have had to work in electronic mediums to pursue at least the financial benefits of living the artist life although, no doubt, some artists have escaped having had to do this.

The novel bogs down in its own dialectic, bit at points it articulates some cogent points about art that's fascinating to ponder. One almost wishes this were Rotsler's Leaves of Grass that he kept tinkering with advancing, revising until it was a masterwork.Still it has much to recommend. What's most fascinating is how this is a doorway into the mind of an era.

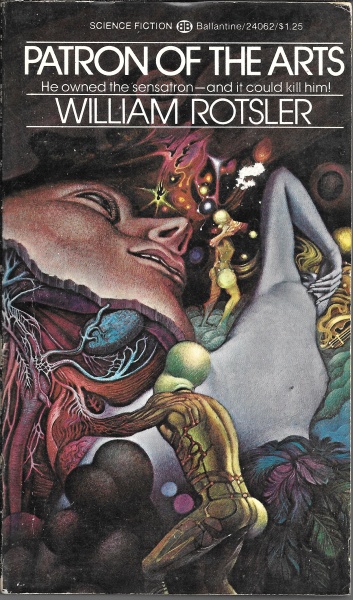

You can see this in the image above, in Fred Pohl's "Day Million", in Terry Carr's "Dancer and the Changer Three" and in the movie Fantastic Planet. They all reach for the ineffable, which is cool albeit at times they purposefully obscure what could be made clear. One part was nudging boundaries wider thanks to "obscenity" court cases like Allen Ginsberg's Howl, which led to others pushing the envelope. Sometimes just putting a thing in a story was enough for some to call it art--no matter the quality. The other part was the Vietnam War and narcotics and reason and defiance of things like story structures and any other reason to offend people gave some reason to call it art. Probably a safe bracket around this era might be 1965-1975.

But it bleeds out a little before and a little after. Take Terry Gilliam's 1981 movie, Time Bandits, for example. The irreverent surrealism of Monty Python lingers, sensing it in 1981. I don't think the former ways were abandoned so much as transformed, altered, shifted. Perhaps too much presence of what might offend was eventually seen as just bad art, and they wanted to refocus on the art of the thing itself. Where Monty Python and the Holy Grail has a cornucopia of brilliant wit, but Time Bandits has the stronger, more unified story. Which is better art? It depends on what you value.

This doesn't mean that because someone bought into one or more aspects of counterculture that they bought into all. William F. Nolan and George Clayton Johnson's Logan's Run, the movie, is part of, speaks for and speaks against such counterculture. It is a fascinating beast. (The novel feels less cohesive, a bit too picaresque, but maybe it might have made more sense if we were reading it in that era.)

This story is Rotsler's one-hit wonder and he mainline's into this vein of the zeitgeist. Probably part of the reason is success in the other arts. In 1968 he has a documentary capturing the culture of its time, a documentary that may have excited Harlan Ellison to collaborate with Rotsler.

The aformentioned style and development as a literary artist and the tapping into the zeitgeist of his day may go some way the lifespan of its reprints ending in 1977. That doesn't mean it isn't a story worth reading, but that it should be read within its context, its background.

Summary:

Brian Thorne, a patron of the arts, has various discussions with the artist, Michael Cilento. Cilento makes sensual portraits of people and transfers them into vivid, technological cubes called "sensatrons." Thorne encourages Cilento to make one of Madelon Morgana, a woman whom Thorne marries and wants immortalized to let others know she is his "as much as she could belong to anyone." As a patron, the art he helps create will make him immortal as well.

Further Analysis:

At least, two musical artists make guest appearances [David] Bowie as a butler of sorts and Earth Wind & Fire as a location (name altered to keep with what the "ancients" once thought to be the four elements of nature).

Cilento agrees to take on Morgana, but only if he can have her in other ways. Thorne assents because he wants the art. The final work becomes the greatest of its kind. Cilento gives the work to Thorne only because Cilento is taking Morgana--an act which haunts Thorne, painful as his surname.

One can see why it was held in great esteem. The ending is emotional, as editors point out, but not necessarily in some profound manner. Effective. It's his ars poetica giving one a sense of art in his time and outside it. If you are looking for stories with statements on art, here's one.

Quotes:

"[Art] was 'mine' only in that I could house it. I could not contain it. It had to belong to the world."

"[Great art] is different each time, for I am different each time."

"[H]e is an artist of his time, yet like many artists, not of his time."

"[T]he reality of art is not the reality of reality."

No comments:

Post a Comment