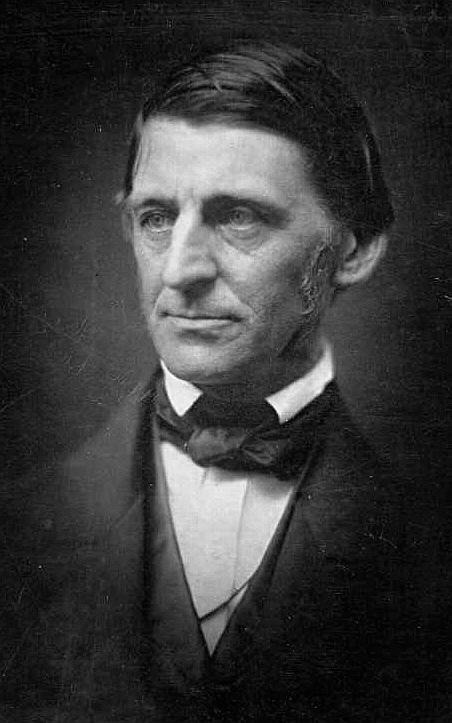

First We Read, Then We Write:

Emerson on the Creative Process

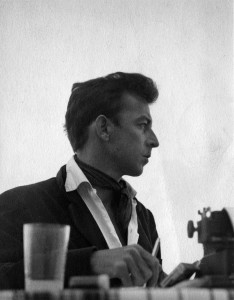

Robert D. Richardson

University Of Iowa Press

As Richardson points out, Emerson is the master of the sentence, influenced by the book of Proverbs. I put up many of his quotes earlier this year (see the Ralph Waldo Emerson tag below). "[Emerson] talked and wrote," writes Richardson, "especially in his journals about the art and the craft of writing. But he never wrote an essay on writing." This slender volume might be considered a corrective. Richardson pillaged Emerson for writing wisdom and collated it into this book--an Emersonian craft-of-writing book, packing more information than most at twice the length. The author even manages to convey a sense of the man behind the writing--and his peculiar take on the art.

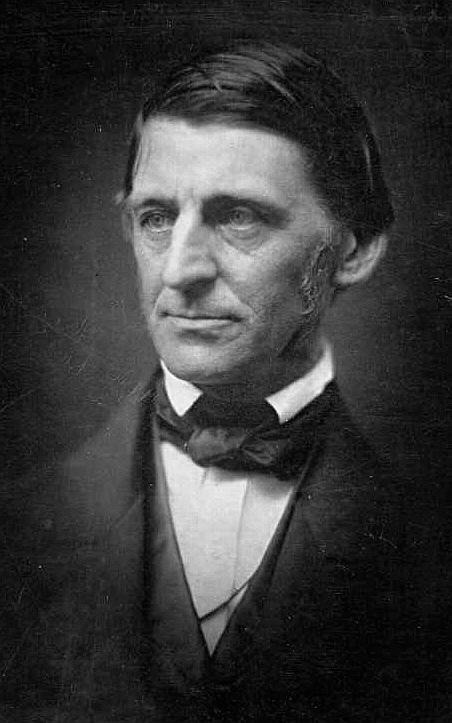

Who was Emerson? Emerson was an essayist and minor poet of the early nineteenth century. He formed a group of Transcendentalists as well as

The Dial. After changing hands, it eventually became a paragon of modernism. Its contents listed a Who's-Who of the era--from T.S. Eliot to Pablo Picasso.

Emerson would encourage the first modern poet, Walt Whitman, as well as Henry David Thoreau. But beyond his wide-spread influence and Trancendentalism, Emerson had much original thought, which Richardson captures much of in the topics: Reading, Journaling, Practical Hints, Nature, Natural Language, Words, Sentences, Symbols, The Art Path, and The Writer. (I have altered titles slightly.)

The first section talks of Emerson's views on reading. He advocated active reading. You don't read widely but deeply. If it is too absorbing, the reader should stop. The reader is in charge of what he puts into his mind. "Each book I read invades me, displaces me." He skimmed until he found something of use, something he found true to himself, and poured himself into that passage. He pointed out that great writers are human, so don't put them on pedestals. He would not read entire categories of literature. Reading was personal, and he accepted as many interpretations as there are readers. Reading was allied with and inseparable from writing, so lazy writers need to be avoided.

The next section treats journaling. He advised Henry David Thoreau to do so, and Emerson's system at first was to make a list of topics to fill in. Later, though, it was random, full of dreams, the best parts of one's life and one's reading.

"Practical hints" are advice such as approaching writing as if it were a battle where you've lost your ammunition and all that's left is throwing yourself at the enemy. He advised writers to write--and without a plan, following an organic form. We should aim for prominent objects, not make something prominent. Writers avoid adjectives in favor of nouns. Writers should not satisfy readers but leave them guessing, thinking. Moreover, coherence and consistency were anathema to Emerson. These are the job of the reader. Failure and inconsistency were part of the game.

We approach "Nature," in the following section, by using words that lead us to symbols. Since words have lost their connection from the nature it sprouted from, it is "the writer's job to 're-attach things to nature.'" Writers leave what is given to us to find the symbol which is more real.

In "Street [or Natural] Language" Emerson wanted to capture the world as it is lived, not that he wanted to live the life of a common laborer, but to capture the man's essence.

The "Words" Emerson disliked were abstractions, polysyllabics, and the wrong word. "[I]n writing, there is always a right word, and every other that is wrong."

On "Sentences", Emerson writes, "[E]very new sentence brings us a new contribution of observation." Because of Emerson's love of the sentence, he moved away from essays to sentences not unlike those in Proverbs. But he also played games where he reversed expectations.

The poetic effects "Emblem, Symbol, Metaphor" stretch toward the spiritual. And humans, even, are symbols. The text refeerences Paul Scott's use of this in his Raj Quartet.

Emerson considers his "Audience": "You must never lose sight of the purpose of helping a particular person in every word you say." In fact, Richardson suggests that Emerson gained his style from public speaking. In "Art Is the Path" Emerson values process over product. He believes all men are creative but only half a man if he does not access it. Finally, "The Writer" discusses Emerson's influences and influencing, as well as his place in the canon.

I have no complaints. It's an excellent little book to spur the writer, the historian curious about the nineteenth-century thinkers, and fans of Emerson.

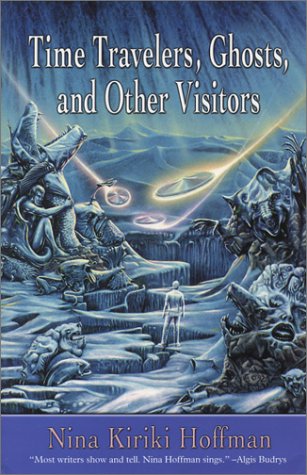

Time Travelers, Ghosts, and Other Visitors

Time Travelers, Ghosts, and Other Visitors