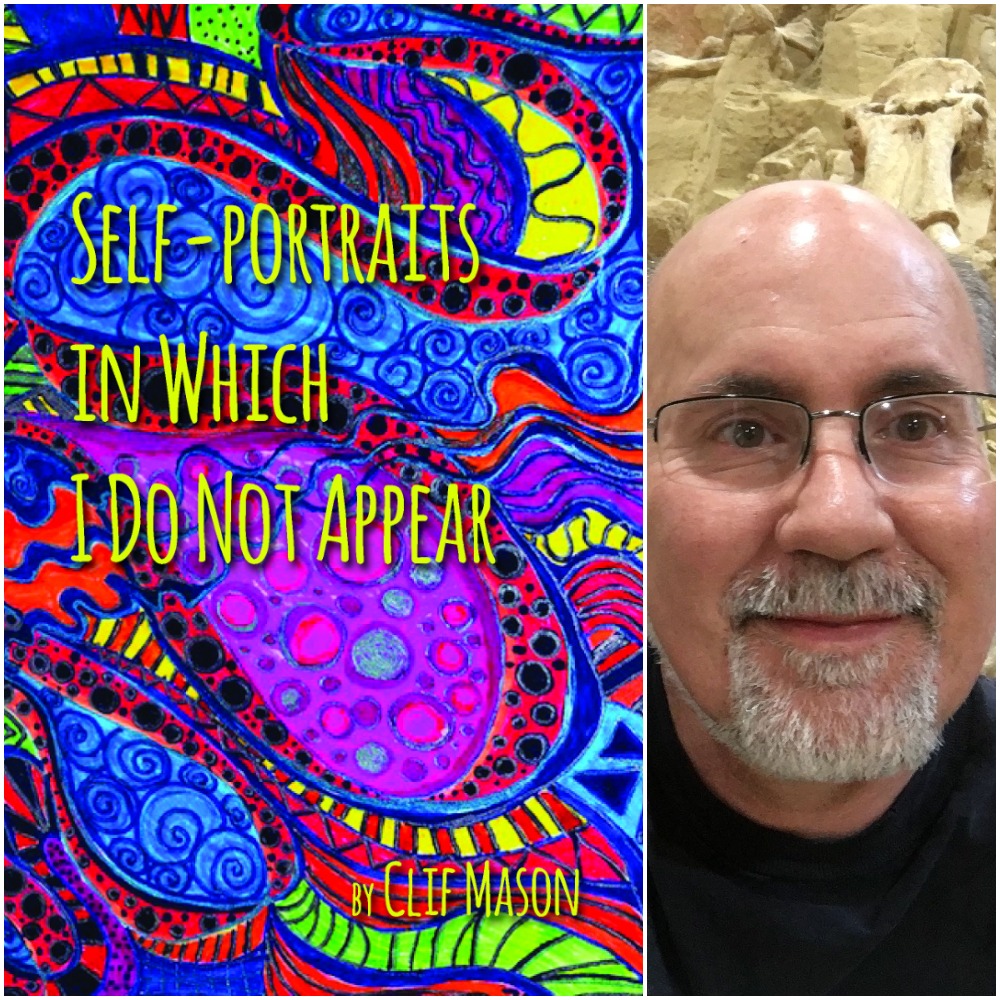

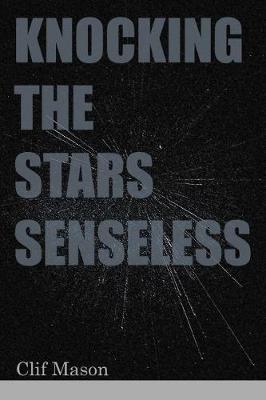

Clif Mason is an English professor and a poet with four collections published. I reviewed his remarkable debut full-length collection, Knocking the Stars Senseless, here and here (part II of the review). Since then, we've been emailing back and forth the following extensive interview on the art, craft life and development of the poet.

This interview is in four parts:

What are the critical pieces of a

good poem?

For reasons I’ve already elaborated, sound and image. To

these I would add line breaks and enjambment, which allow lines and stanzas to

gain in power and meaning through the special intentionality and emphasis they

embody. A poem comes into being when all of these elements become unified and

coherent—mutually cognizant and supporting—thereby gaining its own unique

momentum and force. That is to say, when the poem becomes a living thing, with

its own circulatory system and tissues and organs and networks of nerves.

As I pointed out in the review, you

do extensive revisions, changing not only the poems drastically, but even what

poems go in. How do you approach revision in your poems? In your three newest books?

Poems can fail in a “thousand thousand” ways, to paraphrase

Shakespeare. The desire to revise comes from an acute awareness of those

failures. For me, as for so many others, I’m sure, the ecstasy of composition

is often followed—the next day, the next month, or the next year—by dismay,

disappointment, and sometimes dejection. Being of a naturally sanguine

temperament, I don’t care to live for long in dejection, so I set out swiftly

to revise. I give myself enormous freedom in the revising process. I recast

long-line poems in o short-line ones, and sometimes back into different long

lines. I recast formal poems as free verse and sometimes as prose poems.

There’s something I like about hiding the original formal nature of a poem

inside prose. I intermix other fragments of a like gesture and sensibility into

a poem, and as I’ve said, I combine two, three, or even more poems together. I

let these new versions sit for a time and then I revise them as ruthlessly as I

did the original poems from which they grew. I do the same thing when

fashioning a book. In a sense, the book is a long poem, and the individual

poems its lines and stanzas. At the Colrain Poetry Manuscript conferences that

I attended in 2012 and again in 2014. I had great teachers—Carmen Giménez

Smith, Jeffrey Levine, Martha Rhodes, and especially Joan Houlihan, the Colrain

founder and director. From these mentors I learned to place my best poems at

the beginning of a book and at the end, and then to demand that the poems in

the middle meet that standard of quality. In other words, every poem has to

matter in a book; each poem has to earn its place. Of course, I continually

reappraise my poems and shift my perception of which of them is “best.” I also

tend to tie groups or sections of poems in a book together by theme. And as

someone who is addicted to variety, I try to create a mixture of poems in

different forms and of different lengths throughout a collection. One can, of

course, revise a manuscript forever, moving poems in and around and out and

sometimes in again. At some point, one intuits that one has to stop and accept

that the book has found what is perhaps its best possible form, given whatever

limitations I have as a writer. This was true of Knocking the Stars

Senseless and of my chapbook, Self-portraits in Which I Do Not Appear.

The Book of Night & Waking, my book-length poem, is different in

that it tells a magical realist story of the protagonist, who, despairing

because his country is entangled in war and blackened with grief, sets out to

walk to Antarctica. Along the way, he experiences both great evil (one of the

sections is based on the femicides of Ciudad Juárez, Mexico) and great beauty.

The poem is ultimately an epic love poem, as he connects magically with his

wife (who is not accompanying him) along the way and reunites with her finally

in Antarctica. I found places in the journey for a few poems that had been

published separately (though I revised and re-shaped them for the purpose), but

much of the book is an original composition. This book is also unique in that

it is composed entirely in spaced broken lines that flow down the page.

I know you have interest in fiction

as well. Do you have other books you're working on now--poetry, fiction or

otherwise?

Yes, I’ve completed another full length collection, whose

working title is Tell Me a Story. I’ve selected poems from it to send

out also as a chapbook (provisionally titled Dream Outside of Time). I’m

also taking the draft of a dark fantasy novel that I wrote back in 2010 and

completely rewriting it, based on new conceptions of its narrative

possibilities and new visions of the characters and of the world they inhabit.

I’ve also started writing another novel that will be set in a parallel

universe, on an Earthlike planet called Oceanus, under a black star called

Obsidian. The protagonist of the first novel, a dark priestess named Wing, is a

major character in the second. I love Chinese wuxia films, and I am

planning to include wushu martial arts in the second book, as well as

other fantastical elements.

How many collections do you have out

now and from where? What has yet to be released? Can you describe them for us?

These are my collections: From the Dead Before, Knocking

the Stars Senseless, Self-portraits in Which I Do Not Appear, and The

Book of Night & Waking. The first is no longer in print, as Lone Willow

Press ceased to exist upon the death of Fred Zydek. From the Dead Before

consists of fairly straightforward poems, often about the natural world. The

other three employ natural imagery but are often written, as I’ve noted, in

surrealist and magical realistic modes. Tell Me a Story resembles them

in this way, and one of its sections is composed of magical realist stories. I

have a certain amount of uncollected work from my first 30 years as a writer.

Those poems haven’t fit into the schemes of the collections I’ve fashioned. Should

there ever be a Collected Poems—which is purely hypothetical at this

point—they might find a place after all.