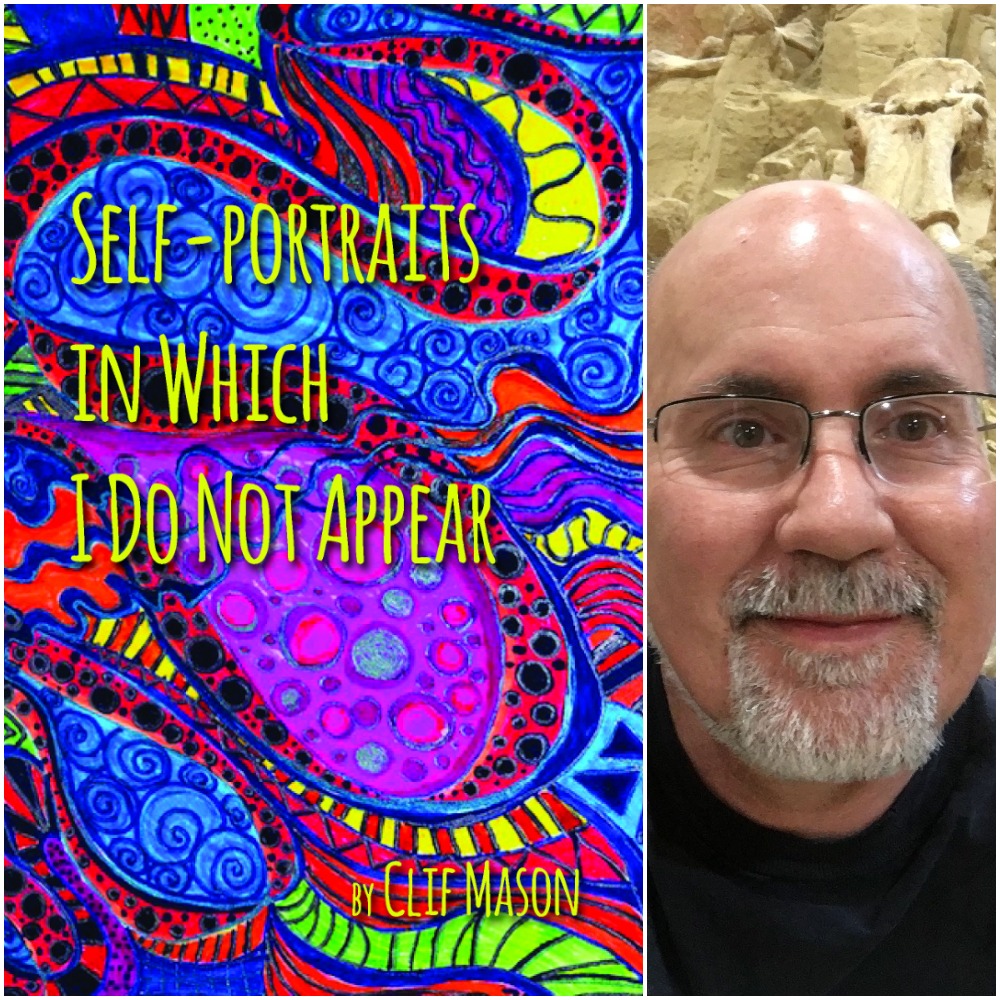

Clif Mason is an English professor and a poet with four collections published. I reviewed his remarkable debut full-length collection, Knocking the Stars Senseless, here and here (part II of the review). Since then, we've been emailing back and forth the following extensive interview on the art, craft life and development of the poet.

This interview is (or will be) in four parts:

One of your stylistic penchants is

the pairing—often novel or unexpected, often tied intimately in image and

sound. Here’s a spectacular one:

There has

been another mass murder

in an

American town.

I try to

expect nothing of flesh or dust

We know immediately what you mean (although sometimes we have to work harder to plot the connections between the sentence/lines/paradoxical pairs themselves. It is simultaneously both amazingly simple and amazingly complex. Here we have images of both life and death that feeds opposingly yet synergistically into the sentence.

How do you settle on a pair? Is it a

tedious process of sorting through possibilities, or is it a natural quirk? Can

you explain this or a pairing that was difficult to settle on?

These pairings come naturally. Some are suggested by

alliteration, some are suggested by image and meaning, as is the case with the

example you quote. If one trusts the organic nature of the process, one has

faith that meaning will obtain. “Depression” is a poem particularly rich in

these pairings, as they flesh out the anaphora that is that poem’s primary

technique. That poem flowed out in a single extended rush. I ended up cutting

some lines and “trainwrecking” in another poem, but the anaphora parts read

very much as they emerged. Some of these make immediate sense, some are still

mysterious to me. An example of the latter is these two lines: “of rust &

riots, rampages & impulse purchases, / of malarial fevers & red planet

hallucinations”. The first of these lines generates speed and momentum and

gives the sense of zeitgeist under great pressure. The second line expands upon

that but in a way that is more suggestive than perfectly rational. I can’t say

that I understand these two lines completely, but I felt they fit the mood of

the poem, so I left them in.

Often neglected in discussions with

poets is the statement. You have a command of imagery, which we expect in

modern poetry, but there’s also the bold statement, the proclamation, memorably

worded. Famously, there’s James Wright’s “I have wasted my life” ["Lyingin a Hammock at William Duffy's Farm in Pine Island, Minnesota”]—that line that

makes the poem peal throughout the images. And of course, William Butler Yeats in “The Second Coming” took on the best and the worst: "The best lack all conviction, while the worst / Are full of passionate intensity."

One of your memorable statement

lines reads:

This is

the age of amputation.

We learn

to live with less and still less.

How does one come up with such

lines? What makes them resonate? Do you have to tinker much with these? Do you

find yourself taking many out, or adding some in? How does/should statement function

in modern poetry?

I am by aesthetic temperament ambivalent about statements

and I try generally to eschew overt didactic statements. That said, there are

statements in my poems. The lines you quote flow directly from the four

preceding lines, which offer images of missing body parts, including a “trunk

of moldering toes.” The direct statement takes these specific images and

creates a larger perspective within which they might gain meaning. The danger

in such statements is that the larger perspective may be a distortion. If such

lines flow out onto the page, one has to pause to ask if they are genuine and

real. If one is at all suspicious of their veracity, they should be cut. In

this case, I felt that the statement reflected something I felt about the

contemporary world, that more and more human meaning is cut away from our lives

by economic and political forces before which we often feel more than a little

helpless. There is certainly a place for the didactic in poetry. Without it, we

wouldn’t have poems like Wilfred Owen’s “Dulce Et Decorum Est,” Adrienne Rich’s

“Rape,” Carolyn Forché’s “The Colonel,” or Rita Dove’s “Parsley”—all of which

are necessary and important poems.

I’m interested in your motifs like

“stars.” Before I understood what you were up to and discouraged you from using

them, did you cut them, did you hesitate, or did you stand up for them,

confident in what you were up to (i.e. “That schmuck doesn’t know what I’m

doing)? Did you take them out and put them back in? When did you realize this

would be an important motif in your works? Did you know what they signified during

the composition of the first poem? or after several poems? or as you were

assembling the manuscript? How do you know what to keep and what to cull?

The incident to which you refer

was when I thought I might be able to use star imagery to link every poem in a

book. I think you were objecting to the surfeit of such images. The word “star”

began no doubt to cloy on the tongue. That was helpful in that I realized it

was perhaps asking too much of a single image to unify an entire book—though

Rilke is able to do it with great power in the image of the angel in Duino

Elegies. The danger was that using stars in this way could become almost a

gimmick. I began as a nature poet, and I realized early on that certain

primordial images—rivers, stars, stones, and trees—were an important aspect of

the way I approached and processed the world. This is probably rooted in my

early years on the family farm and in my high school years in Pierre, South

Dakota—a town in which the Missouri River looms large in the consciousness of

the people who live there. I hope that I use such imagery in fresh and

suggestive ways. So, to answer your question, I certainly took another look at

the poems in which stars figured. I didn’t remove them, as I felt they were

aesthetically justified, but I certainly re-examined them.

As memory serves, can you guide us

through the original stimulus of writing a poem, to composition, to revision

for publication, to revision for the collection? (If pressed for a poem, I’d

say, “Thanksgiving Song” but whatever you have clear in mind is fine.)

“Thanksgiving Song” was originally

titled “Praise Song,” and under that title it appeared in Writers’ Journal.

I had entered it in one of their contests, but the line limit for the contest

was 24 lines and the poem was 45 lines. I had faith in the poem and thought it

might be equally effective if I combined many of the lines. I might say that

I’ve never shied from re-considering the lineation in my poems, as attempting

new line breaks often reveals new possibilities for the poem to make meaning.

The resulting poem came in, as I recall, exactly at 24 lines. In the original

composition, the poem flowed out associatively pretty much as it now reads,

with one exception. A few years ago, I revisited the poem and cut what had been

a whole stanza in the 45-line version of the poem:

Yet the tree frog

wants praise.

Horned owl and muskrat

want praise.

As do red wolf, mule deer,

armadillo, coral snake.

They feel it, know it,

in blood and ravening gut.

The reason I deleted this stanza

was because it seemed flat and prosaic in comparison to the imagery of the rest

of the poem. Cutting this stanza improved the poem. It was at that time that I

changed the title of the poem. I tried further new line breaks, as I felt that

some of those in the 24-line version were somewhat arbitrary. The resulting

poem was 27 lines. It was in long blocks without white space, and I felt it

needed some room to breathe. So, I tried dividing the poem into three-line

stanzas, and that became the poem’s final form.

Lone Willow Press published a very

different chapbook of yours in the 90s. You waited twenty years before doing

another. What was the delay? What made you alter your voice so drastically?

From the Dead Before

was a book that combined some of my free verse nature poems and some of the

formal poems I wrote in the 90s as an attempt to create new possibilities for

my poems. Brad Leithauser’s books Hundreds of Fireflies and Cats of

the Temple were significant influences on my writing at that time, as were

the poems of Marianne Moore, Elizabeth Bishop, Robert Lowell, and Amy Clampitt.

There are a good many sonnets in that collection, as well as a glose (the title

poem). I tried my hand at many other forms in those years, and there was a

sense of adventure and a zest that came from the discovery of the demands and

challenges of received forms, whether it was a pantoum or sestina, a ghazal or

villanelle. However, I stopped writing in received forms when I began to feel that,

for me at least, the form should not be the trigger of a poem. As I’ve already

noted, my poems worked best when words and images appeared in my consciousness

and I allowed them to take shape without loss of their essential mystery. This

is what Keats called “Negative Capability,” which he stated occurs, “when a man

is capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable

reaching after fact and reason.” He thought Shakespeare possessed this quality

“so enormously,” and I agree with him. I don’t claim to achieve this every time

I write a poem, or even consistently. But I certainly aspire to it.

No comments:

Post a Comment