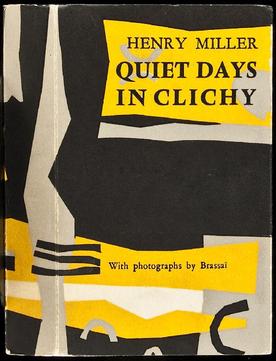

I ran up against this in this short novel, Quiet Days in Clichy, a misnomer, which apparently Miller knew when he chose it. I picked the novel up because it was short, and I was grooving on Miller's observations of people and certain stylistic passages that passed muster for poetry. But here, I had to ask myself why I was reading this.

Where some of his narratives fail to cohere, here it was a more traditional cause-and-effect although it was told out of order for no reason I could fathom. Apparently this has been filmed twice, in 1970 and 1990 (IMDb: 5.4 and 4.9, respectively). The second half of the book (minus Colette) was also filmed and fared slightly better at 5.7. I'd probably pass on them. I'll include trailers here for the curious, but fair warning: the 1970 version displays in abundance a word many find distasteful. The second one is also NSFW.

The narrative might go something like this: Two impoverished writers look for money, food, and sex with prostitutes. Along the way, Carl picks up an underage girl whom they call Colette and who then lives with them. The narrator finds little merit in the women they pick up, or if he does, it's an almost strange ineffable-ness.

What is interesting is actually left outside the narrative: The underage girl is described as a doll, maybe dull, dim-witted. However, I kept wanting to look around the limits of the narrator to see who she really was.

From what little we get of her, she seems dreamy, lost in reverie. She'd disappear. Sometimes for days. Obviously free to do as she pleased, she comes back. One day the men follow her, and she meanders on long walks, contemplative. She sticks with the men. Whatever they have is apparently superior to whatever her presumably rich mother and step-dad have. What is that?

There's something sad in that: to prefer the company of two destitute men, perhaps to carve out one's independence and domestic bliss with men who probably had less interest in her domesticity although apparently they enjoyed it to some extent. Interestingly, the parents know Carl has committed a crime but don't prosecute. Why? What would prosecution bring to light that they don't want raised? Or are they of a more morally relaxed bent? What drove Colette out and that she was willing to return to (not that she may not leave again) or had she been caught on her wanderings? I can't help picturing her mind on those walks dreaming about a better life, or maybe she thought that this would become a better life, eventually

This raises the question of what makes good art. What is obscenity or porn without merit, and what is "literature with erotic motifs?" I just discovered that phrase in comparing this to Vladimir Nabokov's Lolita since both involve similar subject matter. That phrase belongs to Nabokov in this case as it hints rather than displays. However, Miller goes beyond that.

Back in the 20s and 30s there seem to have been a number of novelists like D. H. Lawrence, James Joyce and Henry Miller who were challenging what could be included as literature. For some reason in the 50s and 60s, we as a society loosened up our morals and opened the gates to sexual situations in literature, citing the First Amendment for free speech.

As a person with biological and literature training, I find this natural. How does this impact character relationships? For me, this is the dividing demarcation between art designed to make us think and work that is designed to stimulate and be sold.

I read five pages or so of porn novel in Junior High. We were in a hotel lobby and a fellow swimmer had ducked into a hall and discovered a vending machine with porn novels in it. He bought one and ended up with two copies. This stirred conversation in the room as the books circulated, and of course, I had to read it. It was non-stop "action" thriller, which meant the author had to come up with some bizarre stuff to maintain the reader interest. Obviously, since I read only five pages, the stuff was a little too bizarre.

If that is a marker of porn, then Quiet Days isn't porn, but it is one step below. Because it's Miller, I want to dub it literary erotica, but I don't know that it merits "literary" if I were to follow my own definition above. It fails to focus on language. There is some interesting observation of characters, but rather like a weak tea. This landmark case of Miller vs. California [different Miller] redefined what obscenity was. A number of famous novels have apparently been deemed as obscene in the past, some of which might surprise you.

The new way to configure obscenity were three ideas:

- whether the average person, applying contemporary "community standards", would find that the work, taken as a whole, appeals to the prurient interest;

- whether the work depicts or describes, in an offensive way, sexual conduct or excretory functions, as specifically defined by applicable state law (the syllabus of the case mentions only sexual conduct, but excretory functions are explicitly mentioned on page 25 of the majority opinion); and

- whether the work, taken as a whole, lacks serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value.

Does this novel pass muster? I'll leave that to you to decide. If you've read it, what did you think?

I discuss two other Henry Miller novels:

No comments:

Post a Comment