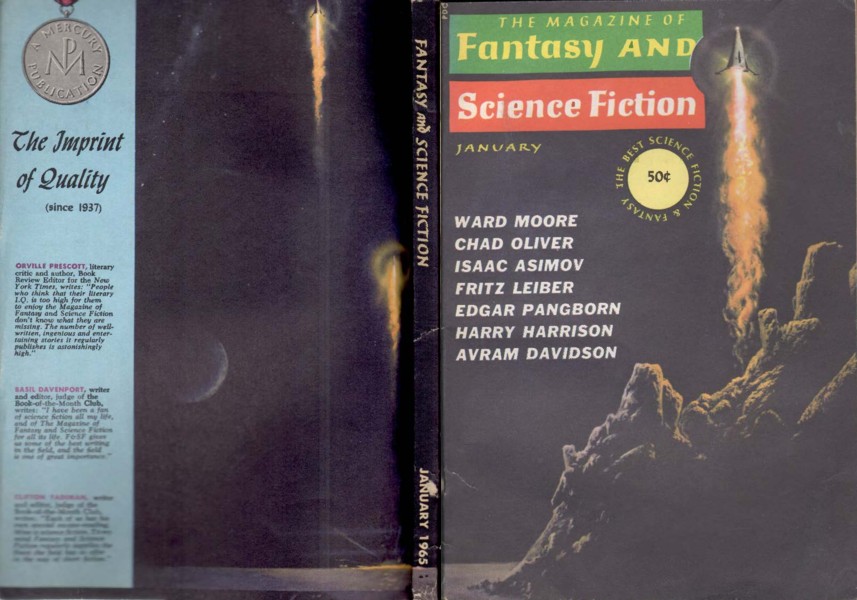

First appeared in Joseph W. Ferman's The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. Up for the Nebula award, it was reprinted by Edward L. Ferman, Martin Harry Greenberg, Carol Mason, Patricia Warrick, Brian Attebery, Ursula K. Le Guin.

Summary:

Two couples of colonists (one pregnant) arrive on a planet and find a road that leads to a castle [they seem uncertain if that's the correct term]. They want to build a house beside the Blakeneys's, a very strange extended family--presumed to be inbred after living alone together for so long--speaking a pidgin language. The Blakeneys came here to escape persecution.

When the foreigners arrive, they are welcomed. But then the new colonists go to build their own house. The Blakeneys seem less responsive, the new colonists borrow a few necessities and promise to repay. The foreigners plan to have their kids intermarry to avoid the Blakeneys for a time, but eventually they'd have to marry to improve genetic rigor.

Discussion (with Spoilers):

We are meant to think of the nursery rhyme "This Is the House That Jack Built," which is a cumulative tale. This sort of song opens simply, gradually accruings wilder and wilder causalities until it becomes the Butterfly Effect, where a flap of a butterfly's wings causes a typhoon halfway around the world.

The parallel here is similar in that what we are initially given is a simple family who seem to welcome new colonists when they are a part of the family or home. But as soon as they have a house apart from theirs, they attack. The chain of causality is not immediately apparent, but there seems to be a critical system of governance that has been violated making the new colonists worthy of death. With some irony (or maybe none, that is, it is part of the causality), the Blakeneys now persecute where before they were persecuted. Or were they? Was it their behavior that caused people to persecute them?

Perhaps one could leave it there, but this introduces the central issue with the Norton anthology. This is a strong tale. And the verbal pyrotechnics are a joy. I would not protest reading this in a Norton, but it doesn't establish what's going on. What an anthology purporting to establish SF as a field. What does that mean in other Nortons? Usually, one establishes the various movements and the major players.

Where James Gunn's anthologies succeed where others do not is that he grabs the central works that made people talk when they appeared. Le Guin's is more of a side-bar: Hey, these were good, too. Le Guin's can only work if you establish what the main line SF is.

Only if and when you do that does this story gain more power. True quill SF establishes colonies. People work together. They build a community. That's what the new comers plan to do. The older colonists look like a group who has fallen into disrepair--in knowledge/know-how, in language, and in social etiquette. The new comers expect--as most readers might as well--that they have knowledge to trade with the older colonists that they might grow together and strengthen the community as a group. That this expectation is thwarted makes this story novel and provides context. This is the main quality lacking in this anthology. If you have a story that thwarts an expectation, first we need a story that creates such expectations. We can't assume, which is sort of the point of the story: assuming others expectations/knowledge (or lack thereof).

No comments:

Post a Comment